The short answer is that the Affordable Care Act changed all of the rules. Younger, healthier small groups, which historically have been rewarded with below-average premiums for their relatively low claims risk, can expect their costs to go up under the new modified adjusted community rating rules. The community rating guidelines do not permit medical underwriting in the small group market, so healthier companies are being forced to pay more in order to offset the costs of older, sicker groups. It’s not fair, but it is reality.

Self-funded plans offer a great alternative: healthy companies are able to dodge the new rules and might even get a refund if they have a good year. Still, not everyone is sold on self-funding, and some companies won’t actually benefit.

For instance, a company with 25 employees might have one worker with a serious medical condition. Under a partially self-funded arrangement, the employer would cover a portion of the cost for that employee, up to a stop-loss amount, at which point the reinsurance would kick in and cover the remaining amount. Unfortunately, the expected claims costs for this employee will be reflected in the rates, so the company will pay a higher monthly amount if it’s not declined altogether.

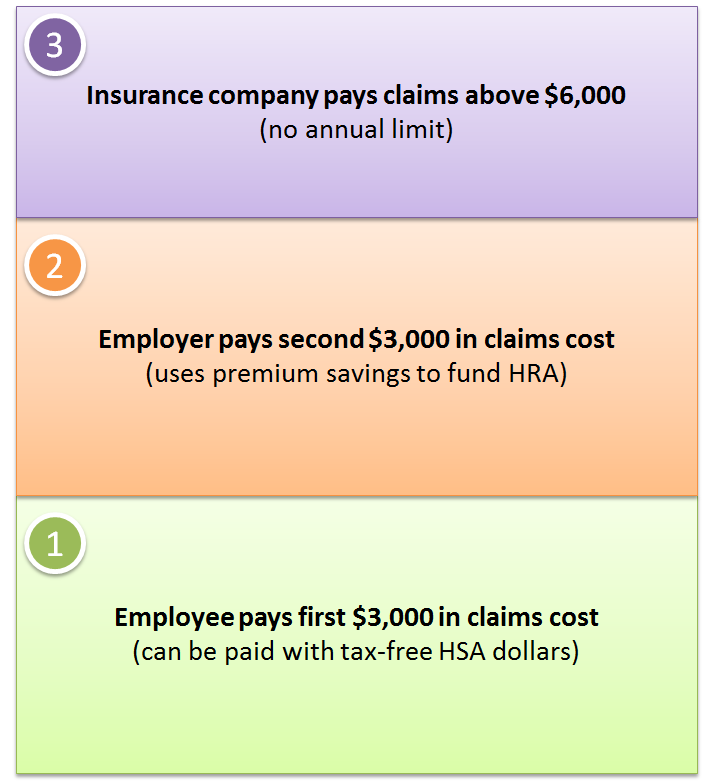

There is another option, though. The employer can purchase a fully-insured plan in the small group market, where it won’t pay more for the sick worker, and “self-insure” a portion of the out-of-pocket costs with a Health Reimbursement Arrangement (HRA). Sure, the employer will incur some predictable HRA claims on that one employee, but if the rest of the company’s employees have a good year the employer could still come out ahead. Perhaps it will help if we put some numbers to it. We’ll keep the math easy.

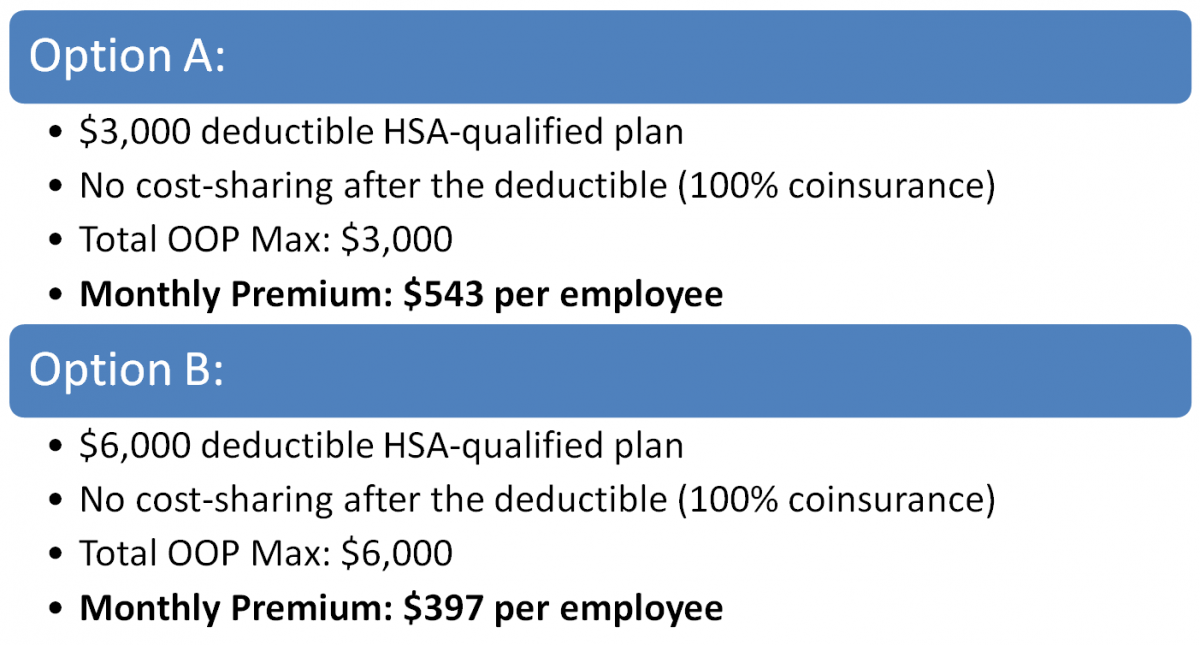

Assume the company has these two options: stick with its existing $3,000 deductible HSA-qualified plan or purchase a higher-deductible plan and use a portion of the premium savings to lower the exposure for the employees.

One option would be to sink the premium savings into the employees’ HSAs. Sure, the employees would have more exposure than with the lower-deductible plan, but they’d also have some money for first-dollar coverage, which isn’t a bad trade-off. Unfortunately, the employer wouldn’t save any money with this option.

Another approach, though, would be to use the premium savings to pay for a Health Reimbursement Arrangement. The employer could reimburse claims between $3,000 and $6,000, making the plan “feel” to the employees like a $3,000 deductible plan. It would still be HSA-compatible, and since the employer is covering 100% of the premiums, the employees could certainly contribute some of their own funds to a Health Savings Account.

One final thought: This is not necessarily the way we at NueSynergy would have designed the HRA (we would have been a little more creative), but this example does illustrate that there’s still a place for HRAs in a community rating environment. By self-funding a portion of the deductible, a company can reduce its fixed monthly premium while maintaining a great health plan for the employees.

If you have a client you’d like to consider an HRA for, we’ll work with you to structure it in a way that will minimize employer risk while maximizing employee satisfaction. Contact us today and let’s take a look at one of your toughest clients.